A few days ago, the Boston Globe declared that a new study found that “Black drivers [are] pulled over in Boston at 2.4 times the rate of white drivers… in stark contrast to statewide research conducted by the Massachusetts public safety office that found ‘no support’ for racial disparity.”

This is false. The two studies are not in stark contrast. In fact they are entirely consistent (as I’ll explain below). Indeed the new “study”, if it can be called that, did not find much new at all. It appears to be a simple restatement of the broadly recognized trends in data about police stops, minus any analysis about causes. The organization that produced the “study”, Vera, describes itself as a group consisting of “advocates, researchers and activists working to end mass incarceration.” Advocates and activists. Going forward, I’ll refrain from following the Boston Globe’s lead, and refer to this as a policy paper rather than a study because it did not advance our knowledge about police stops. Rather, it advances a policy proposal.

Importantly, this was a policy paper with a sort of official government imprimatur. According to the paper, “The Vera Institute of Justice’s (Vera) Reshaping Prosecution program partnered with the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office (SCDAO) from July 2020 to March 2022 to study racial disparities in the criminal legal system.” So, its claims will likely have an impact on public policy.

What did the paper actually say? The main “finding” was that

“Police disproportionately stop Black drivers in Suffolk County, especially for non-traffic-safety reasons. Police pull over Black drivers at 2.3 times the rate of white drivers for non-traffic-safety violations, such as improperly displayed license plates or a single broken taillight.”

This was roughly the same result as found by the Massachusetts study that I discussed in a previous post, and by many other previous studies. Black drivers are pulled over at a greater rate. But why? The previous study provided a clear answer to that question through rigorous statistical analysis of police stop data. It found that during the day, when police can identify the race of drivers, whites were pulled over more often and blacks less often than at night, when police cannot identify race. In other words, police are biased against pulling over black drivers. So, what explains why black drivers are pulled over at higher rates despite police being biased against pulling them over? Much higher rates of driving violations, on average, among black drivers (a fact that should surprise nobody, if driving violations are associated with socioeconomic status, as many types of legal violations are).

So, what did this policy paper contribute to our understanding? Did it use a new methodology that revealed flaws in the earlier study? No. Instead, it mostly ignores the fact that the data clearly shows that police stop black drivers more often simply because black drivers are committing many more violations on average.

By doing so, the paper sidesteps the obvious conclusion: the best way to decrease traffic stops of black drivers would be to increase compliance with traffic laws among black drivers. Ignoring this obvious conclusion provides cover to argue for an approach diametrically opposed to addressing the root problems. The paper proceeds to investigate which types of traffic violation police could stop enforcing altogether in order to most reduce the number of black drivers stopped by police!

“Fifteen non-traffic-safety violations are responsible for 46 percent of the racial disparity in Suffolk County non-traffic-safety stops. Vera researchers measured the Black–white racial disparities of each of the 150 unique non-traffic-safety violations. If police did not stop drivers for the 15 non-traffic safety violations with the greatest Black–white disparity, nearly half of the Black–white disparity in non-traffic-safety stops would be erased.”

What were the 15 “non-traffic safety” violations?

Obstructed or non-transparent windows that impair visibility

Falsifying or hiding license plate numbers with “with intent to conceal the identity” of a motor vehicle.

Driving after a license is revoked for being a “habitual traffic offender”—for such things as repeated drunk driving, hit-and-run accidents, endangering people’s lives through reckless driving, etc.

Driving after a license is suspended (including for reasons similar to revocation above).

Driving a vehicle with a suspended registration (including for not having insurance covering injury to others).

Driving a vehicle without working lights, or with lights off during nighttime.

Driving a vehicle without working brakes, braking systems, mufflers, horns, lights, audible warning systems, and other safety related equipment.

Driving without a license plate or with the number obscured.

Knowingly permitting someone without a drivers license or with a suspended or revoked license to operate a vehicle.

Despite the fact that the laws defining all of these traffic violations exist to protect public safety, the “activists” and “advocates” who wrote this policy paper find that these are “non-traffic safety violations”—amazingly including having windows tinted so dark that visibility is impaired, not having working lights, brakes, and horns, driving after your license has been revoked or suspended for repeated drunk or dangerous driving, intentionally falsifying or hiding your license plate number, driving without insurance, driving without a safety inspection, and driving without ever having obtained a license.

The paper proposes a set of policy recommendations including that city councils and police departments adopt policies “preventing police from initiating a traffic stop for non-traffic-safety violations”, and that district attorneys decline to prosecute cases that arise from such stops.

This would be a less concerning proposal coming from a fringe activist group. However, as mentioned above, this policy paper was written in partnership with the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office. The document appears to be less the rantings of a fringe activist group, and closer to an official blueprint for traffic (non)enforcement going forward.

Interestingly, despite the Boston Globe’s claim that “[t]he findings differ sharply from the results of a study published in February by the state’s Executive Office of Public Safety and Security [which] found no evidence for a pattern of racial disparity in traffic stops”, buried at the end of the Vera policy paper is an admission that the differences in traffic stop rates reflect differences in violation rates and not police bias:

“In a recent report commissioned by the Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety and Security, researchers applied a veil-of-darkness analysis to measure racial disparities in traffic stops occurring across Massachusetts from February to December 2020. A veil-of-darkness test seeks to measure officer bias by comparing traffic stops made during the day to those made at night, based on the assumption that police are less able to determine a driver’s race or ethnicity after dark than during the day. Although officer bias and explicit racial profiling are important considerations, Vera’s analysis centers on disparate impacts, regardless of whether an individual officer is engaging in measurable bias.”

This is an implicit acknowledgement that none of the differences in arrest rates are due to bias, and that previous research has already demonstrated that the differences are instead due to higher rates of driving violations by black drivers. The Boston Globes spins this as “the findings differ sharply”, which is false.

Spinning it thus helps to obscure the radical policy being proposed. Instead of addressing the root causes of markedly higher rates of crime and other legal violations in many black communities, we are now told that police should simply no longer enforce the laws that black Americans violate at higher rates. To these activists, the problem is not that those communities are plagued with higher rates of illegal activity—hurting, primarily, the residents in those very communities. Rather, the problem is that police are enforcing the laws that are frequently broken in those communities.

This parallels other developments in Boston. For example, Boston abandoned the use of exams to assess police officers’ knowledge of their jobs for the purposes of promotions. Although nobody even alleged that the exams were intended to be discriminatory, and the court did not find anything at all about the tests that was biased or discriminatory, the fact that black officers were not, on average, scoring as highly as white officers ultimately doomed the test. According to the new racial orthodoxy, knowledge of the law and police procedure is simply not relevant enough to the job of policing to use as the basis for promotions. (Of course, the absence of any finding of bias did not prevent the Boston Globe from labeling the tests “racist” and campaigning against them.)

Similarly, last year Boston dramatically reduced the role of exams in admission to its exam schools because black students scored much worse on average. Rather than try to address the root problems causing many black students to be underprepared for the demanding academic environment of exam schools, Boston is simply re-engineering its admission system to admit less prepared students. This, despite extensive evidence that such racial engineering gravely hurts the underprepared students who are admitted.

Across the board, instead of addressing root problems leading to worse performance by black Americans, we are being told that the solution is to re-engineer our society to do away with the very notions of standards and accountability.

In the case of traffic violations, the Vera policy paper advocates creating an entirely new branch of law "enforcement", not authorized to use force but working in parallel with police officers to encourage compliance with traffic law. Because, as they see it, the problem is not that black communities are plagued with much higher rates of illegal activity, but rather that those communities are subject to too much law enforcement by the police attempting to address that illegal activity. It’s hard to see how a special kind of law enforcement officer that is only empowered to politely ask people to comply with traffic laws, but not empowered to actually enforce those laws, will be an effective way of reducing traffic violations. It’s also hard to overstate the degree of racism implicit in the approach of reengineering our society to lower standards in areas where black Americans are performing poorly.

And, who will be hurt the most from this denial of reality? The answer to that question depends on who benefits most from careful, law abiding, driving. Good driving helps to protect the safety of the driver and the communities they are driving through. Re-engineering law enforcement to reduce application of laws that ensure safe driving to black drivers, who are more likely to be driving through predominantly black neighborhoods, disproportionately hurts black communities and black drivers.

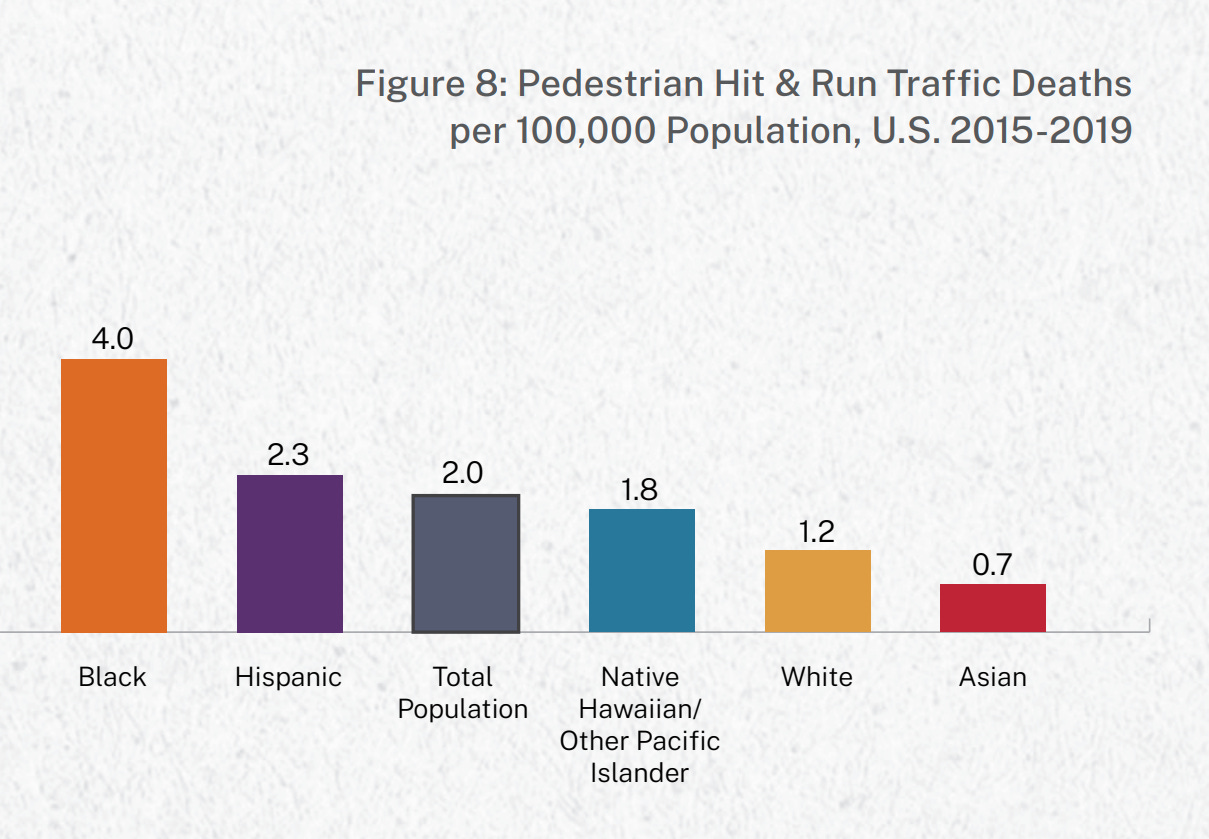

Pedestrian traffic deaths reveal the toll taken by higher rates of traffic violations in many predominantly black communities. The Vera policy report advocates for police to cease enforcing laws that prohibit people from driving after their licenses have been revoked for being “habitual traffic offenders”—for such things as repeated drunk driving, hit-and-run accidents, and endangering others’ lives through reckless driving. Apparently, the Vera activists don’t mind increasing traffic deaths in black neighborhoods that are already suffering from drastically higher traffic deaths due to their higher rates of traffic violations.

The dirty secret about the movement to racialize our public policy is that it is generally black communities who bear the entire burden of these misguided reforms.

I write about cars and anecdotally I've been hearing a lot of stories about reduced traffic enforcement over the past two years. Even in states like Ohio, which is notorious for speed enforcement, speeds are up. Here in Michigan you used to be able to do 79 in a 70 mph zone without worrying about a ticket, now it's closer to 83 or 84. I see a lot more drivers going ~90 than I did before the pandemic. It's not clear if that's because of the pandemic or also because police officers are less vigorous in the wake of the George Floyd case, but anecdote aside, the actual statistics show an alarming increase in the number of black men killed in traffic accidents over the past couple of years.

the evil offshoot of PC, which really needs to be addressed because its consequences are lethal. time to call a spade a spade.